At some point I have to decide that that script is good enough to move forward. That’s a theme that’ll pop up frequently over the course of the project – having to decide that something’s good enough to go on to the next step. There’s always more tweaking that I can do on whatever it is I’m working on. Sometimes it’s hard to make that decision. My perfectionist nature makes me want to work on it until it’s perfect, but at that rate I’ll never get to the end.

So after several revisions I declare it done. Pretty much. Sort of. Actually, I reached this stage a year ago but I still make the occasional change. The truth of the situation is that I can’t help myself from tweaking right up until I start animating the actual animation. Even now, when I’ve already recorded dialogue, I find things that just don’t seem right and I think would be a lot better. The practical upshot is that I’m going to have to have another recording session at some point to record the changed dialogue.

Anyway, getting on with it. (I want to bring everyone up to date so that I can start talking about what I’m up to now.)

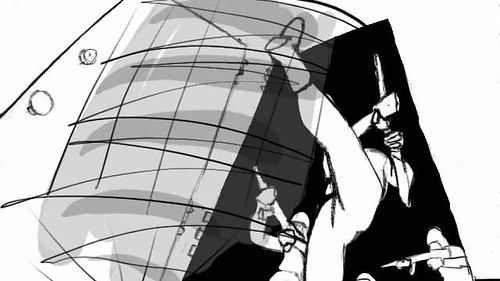

Once I decided the script is pretty good I started making the storyboard. For those of you who don’t know what a storyboard is, it’s sort of like a visual script. I draw pictures of every scene in the film, noting any dialogue and sound effects that are going to happen there. I get down to quite fine detail, having a separate drawing for most of the actions that will happen in the film. This includes character movement, camera moves, facial expressions, etc. Basically, this is where I make my plan for the composition and look of the film.

I do most of my storyboards in pencil on templates that I designed myself. I usually don’t do much shading – most of what I’m planning out is about shapes. I would actually like to do my boards on the computer, but I haven’t found a good program for it. What I really need is something that works kind of like a word processor, except for a series of pictures. The annoying thing about doing it on paper is that if I decide I need to add a scene then I have to use weird numbering for it (the scenes are numbered to help me keep track of them). What’s the number between 16 and 17? 16.5? 16A? And what if I have to insert a new number on either side of that? It would be really useful to have something that automatically kept track of the numbers.

Another problem with doing my boards on paper is that when I move on to the animatic I have to scan them in. If I did it all on the computer from the start then I would be able to skip over that whole step (which would be useful, since I don’t even have a scanner!).

Just like with the script, I showed the storyboard to lots of people. I took it to the Women in Animation Storyboard Pitch Night twice, I think. SB Pitch Night is a monthly event where people bring boards they’re working on and “pitch” them to the other attendees. Pitching involves pinning the pages up to a cork board and sort of walking everyone through the story – describing the action, acting out the characters’ parts, delivering the jokes, and so on. Part of the point of this event is to get practice pitching for studio development people – many of the people who come to Pitch Night want to work as storyboarders in the industry.

In theory my class at UCLA was also a place to pitch my film, but in practice it’s not nearly as useful as Pitch Night. In class you’ve got fifteen or twenty boards to get through in a total of about six hours (actually, it may have been as little as three… I must be getting senile because I can’t remember now. But let’s assume six just to be conservative). That gives just 18 minutes per person, though with all the fussing about that happens in class as well as the time it takes to hang up boards it ends up being more like 10 minutes. What’s more, my boards tend to be a lot longer than those of my classmates, since I go into so much detail. Finally, since board pitches only happen occasionally at school, I think maybe my classmates were timid about giving feedback. After being on both sides of so many pitches over the years I tend to have lots to say about other people’s boards, and I always hope to get the same when I pitch my own.

Okay, this brings up another thing I’d like to tell you about. When I was at the University of Oregon I had the best class and the best teacher of all my time in college (and as most of you know, I spent a lot of time in college). The class was called… um… Elements of Animation or something like that. It was taught by Joe Maruschak, a former student in the animation program.

Now the thing to know about art school, or at least the one at the University of Oregon, is that they never seem to teach composition. Well, I guess I’m overstating the situation a bit. Many professors talk about composition and make some attempt to cover its principles, but not in a way such that anyone actually ends up understanding it. They tend to talk about Organic/Inorganic shapes, Warm/Cool colors, and stuff like that. They assume you know what they mean with these terms – I guess because it comes so intuitively to them. I would say that some people have that same intuition and pretty much get what the prof is talking about, but I didn’t. They don’t tell you what they mean unless you explicitly ask, but not before giving you a look like you’re touched in the head.

Many would say that this felt (as opposed to calculated) approach is exactly right for teaching art. Well, let me introduce you to Rant #47: not all artists rely on intuition – nor should they. The mark of a good artist is that they understand and follow the principles except when they don’t. Until you understand the rules you can’t know when, where, and why to break them.

So, really, no one learned composition at UO. I know this because I heard it in complaints from Joe Maruschak, my favorite teacher. He was frustrated by the fact that all these fourth-year art students came into his class and he wasn’t able to assume a knowledge of basic composition principles. As a result the class turned largely into Basic Composition As Applied to Storyboards and Film. I can see how this would be frustrating for him, as he had probably hoped to teach a high-level class getting into more subtle aspects of filmmaking. For me, though, it worked out wonderfully. Finally, after years of college art classes, I Learned Composition.

The thing is that there are, as I said, principles. There are Rules to learn. This was a revelation for me. After so many classes with touchy-feely teachers who didn’t understand basic technical stuff like how to REALLY draw an ellipse to represent that circle in perspective I had begun to fear that I would never understand the stuff they were trying to teach me. But no! Joe showed me that there are specific, even algorithmic, things you can do in order to end up with a good product.

I know, I know. Art is supposed to be intuitive, right? It’s SUPPOSED to be. You can’t THINK a great work of art. And you’re right, sort of. Do you think Picasso couldn’t draw realistically-rendered portraits? Of course he could! He was an excellent draftsman. His genius, though, was not in his drawing ability. It was how he went beyond that. He learned the basics – perspective, rendering, composition – and then moved beyond the rules. In learning artistic principles he was able to figure out how, when, and why to break them.

Okay, I’m tangenting a bit. Sorry about that.

Anyway, in Joe’s class I learned the beginnings of the principles of film and storyboarding. I continued learning through critique sessions at the UO animation club (which Joe also hosted). The whole time I was working on Pink & Ain’t I would bring working copies of my animatic and animation to meetings and get feedback. Through many meetings I gradually got a better and better feeling for how the rules worked, until I got to the point I’m at now – where for the most part I don’t even have to think about them. When I storyboard many of the decisions I make come naturally. Only when I analyze them after the fact do I realize that yeah, that was the right thing to do according to the Rules. Sometimes I find something I missed and I’m able to use my own analysis skills to correct it. And sometimes I break a rule on purpose. The rules aren’t there to restrict me to the path – they’re just there so I know where the path is, and then I can decide for myself which way to go.

Okay, I gotta stop now. I’ve been writing for more than an hour and it’s past my bedtime. I guess the animatic and voice recording will have to wait until later 🙂